Analyzing Multiple Data Sets

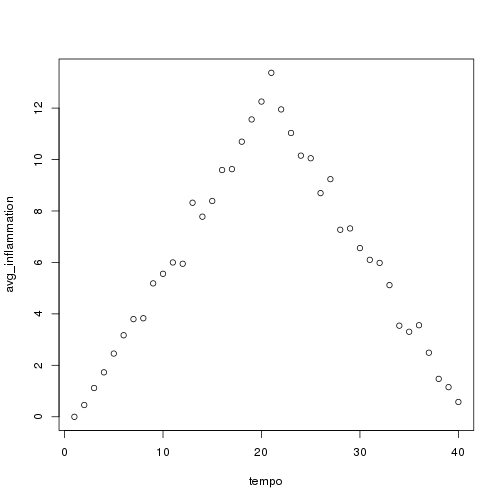

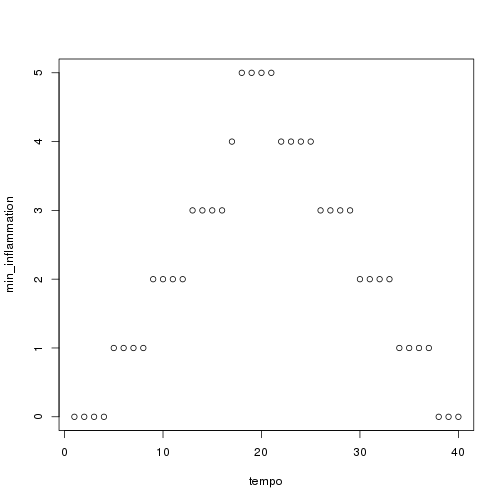

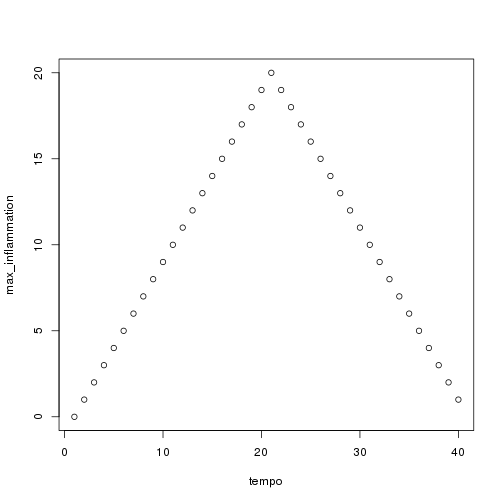

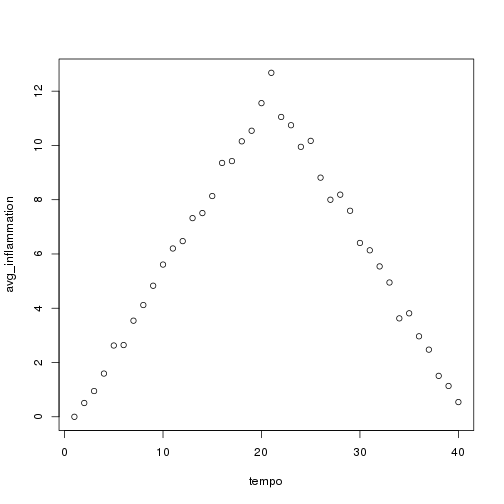

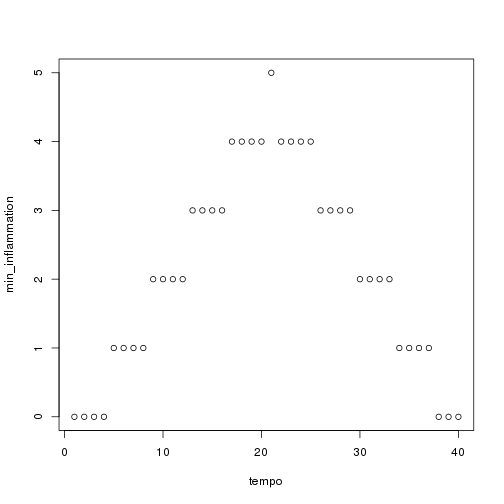

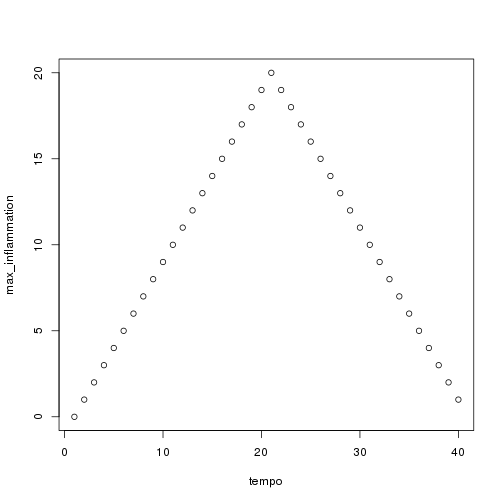

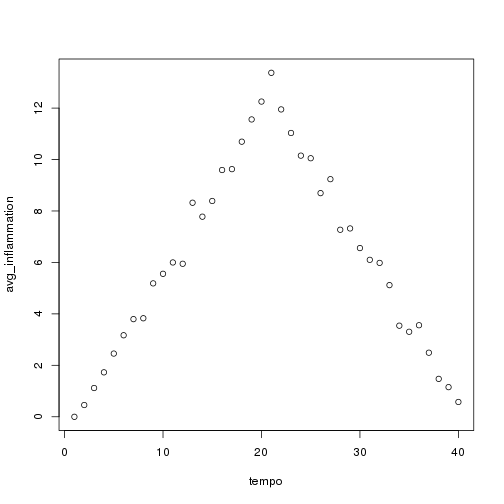

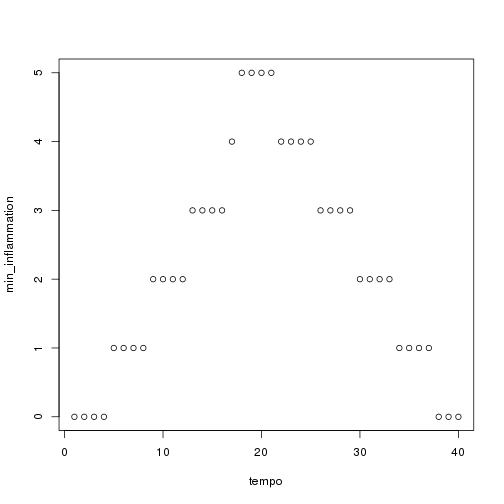

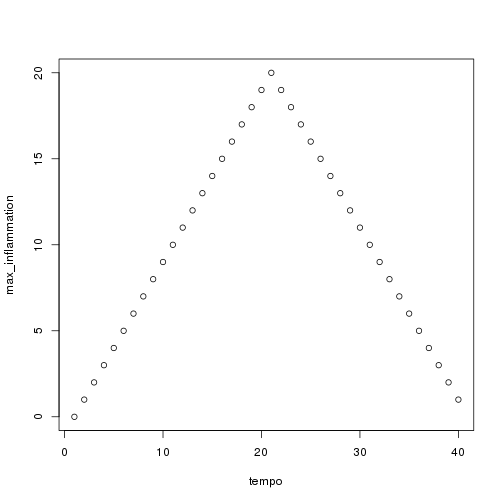

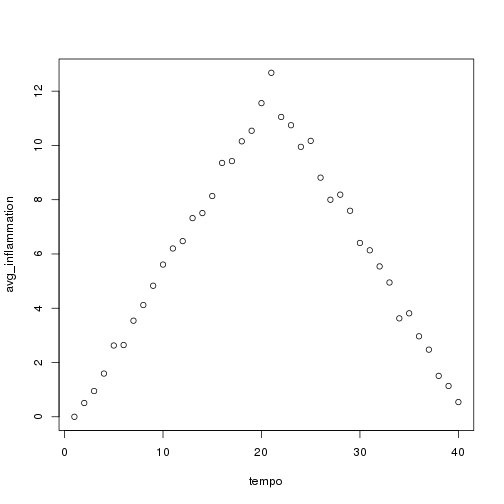

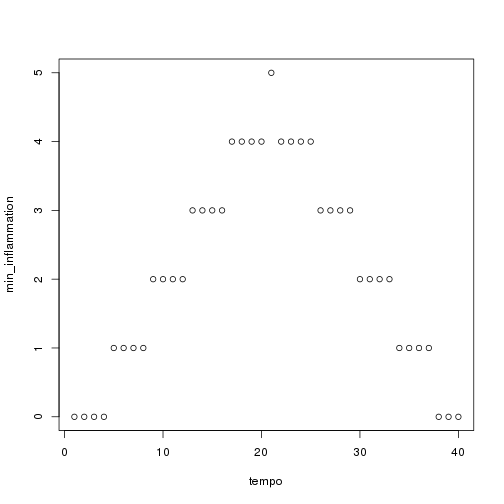

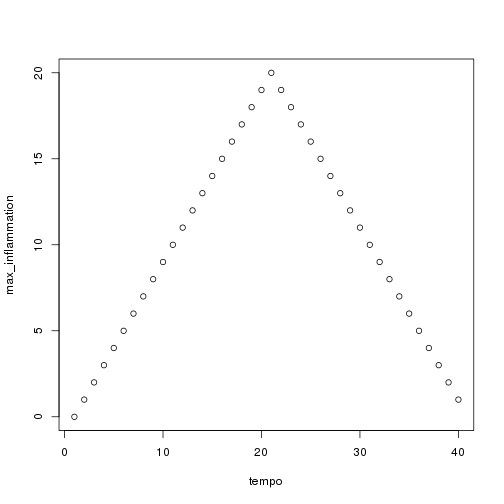

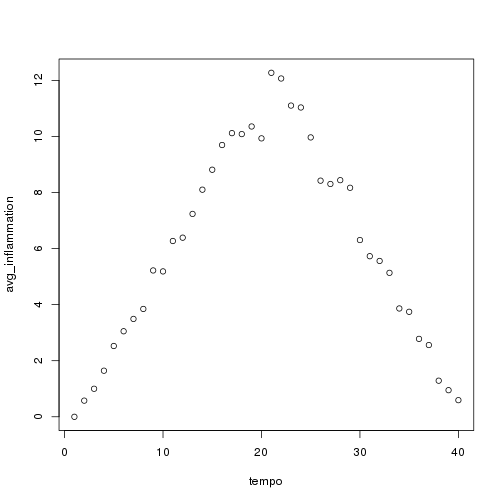

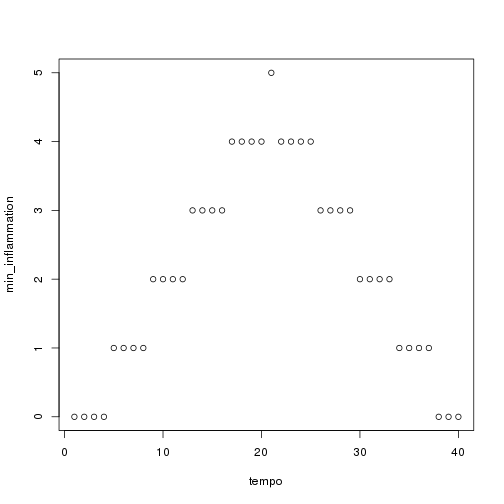

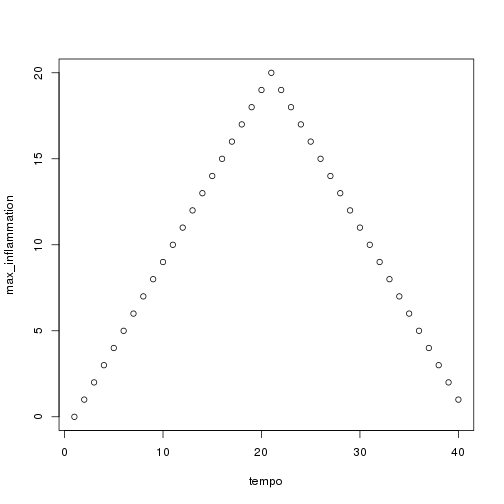

We have created a function called analyze that creates graphs of the minimum, average, and maximum daily inflammation rates for a single data set:

```r analyze <- function(filename) { fdata <- read.csv(filename)

avg_inflammation <- apply(fdata, 2, mean) ## or colMeans(fdata)

max_inflammation <- apply(fdata, 2, max)

min_inflammation <- apply(fdata, 2, min)

tempo <- seq_len(ncol(fdata))

plot(tempo, avg_inflammation)

plot(tempo, min_inflammation)

plot(tempo, max_inflammation) }

analyze("data/inflammation-01.csv") ```

We can use it to analyze other data sets one by one:

r

analyze("data/inflammation-02.csv")

but we have a dozen data sets right now and more on the way. We want to create plots for all our data sets with a single statement. To do that, we'll have to teach the computer how to repeat things.

Objectives

- Explain what a

for()loop does. - Correctly write

for()loops to repeat simple calculations. - Trace changes to a loop variable as the loop runs.

- Trace changes to other variables as they are updated by a for loop.

- Explain what a list is.

- Create and index lists of simple values.

- Use a function to get a list of filenames that match a simple wildcard pattern.

- Use a

forloop to process multiple files.

For Loops

Suppose we want to print each word in our sentence we defined earlier on a line of its own. One way is to use four print statements:

r

pangram <- "the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog"

words <- words <- strsplit(pangram, " ")[[1]]

```r print_words <- function(sentence) { print(sentence[1]) print(sentence[2]) print(sentence[3]) print(sentence[4]) print(sentence[5]) }

print_words(words) ```

## [1] "the"

## [1] "quick"

## [1] "brown"

## [1] "fox"

## [1] "jumps"

but that's a bad approach for two reasons:

-

It doesn't scale if we want to print the elements in a vector that's hundreds long, we'd be better off just typing them in.

-

It's fragile if we give it a longer vector, it only prints part of the data, and if we give it a shorter input, it produces an error or returns

NAvalues because we're asking for elements that don't exist!

r

hello <- c("I", "was", "here")

print_words(hello)

## [1] "I"

## [1] "was"

## [1] "here"

## [1] NA

## [1] NA

Here's a better approach:

r

print_words <- function(sentence) {

for (i in seq_along(sentence)) {

print(sentence[i])

}

}

This is shorter—certainly shorter than something that prints every character in a hundred-letter string—and more robust as well!

r

print_words("oxygen")

## [1] "oxygen"

The improved version of print_words() uses a for() loop to repeat an operation—in this case, printing—once for each thing in a collection. The general form of a loop is:

r

for (variable in collection) {

do things with variable

}

We can name the loop variable anything (syntactically valid). in is part of the for() syntax. Note that the body of the loop is enclosed in braces {. For a single-line loop body, as here, the braces aren't needed, but it is good practice to include them as we did.

Here's another loop that repeatedly updates a variable:

r

len <- 0

for (vowel in seq_len(nchar("aeiou"))) {

len <- len + 1

print(paste("There are", len, "vowels"))

}

## [1] "There are 1 vowels"

## [1] "There are 2 vowels"

## [1] "There are 3 vowels"

## [1] "There are 4 vowels"

## [1] "There are 5 vowels"

It's worth tracing the execution of this little program step by step. Since there are five characters in "aeiou", the print() statement will be executed five times. The first time around, length is zero (the value assigned to it on line 1) and vowel is "a". The statement adds 1 to the old value of length, producing 1, and updates length to refer to that new value. The next time around, vowel is "e" and length is 1, so length is updated to be 2. After three more updates, length is 5; since there is nothing left in "aeiou" for R to process, the loop finishes and the print() statement tells us our final answer.

Note that a loop variable is just a variable that's being used to record progress in a loop. It still exists after the loop is over, and we can re-use variables previously defined as loop variables as well:

r

letter <- "z"

for (letter in seq_len(nchar("abc"))) {

print(substr("abc", letter, letter))

print(paste("after the loop, letter is", letter))

}

## [1] "a"

## [1] "after the loop, letter is 1"

## [1] "b"

## [1] "after the loop, letter is 2"

## [1] "c"

## [1] "after the loop, letter is 3"

Note also that finding the length of a string is such a common operation that R actually has a built-in function to do it called nchar():

r

nchar("aeiou")

## [1] 5

nchar() is much faster than any R function we could write ourselves, and much easier to read than a two-line loop. We can also use length() to tell use the number of elements in a vector, the number of columns in a data frame, or the number of cells in a matrix.

Challenges

- R has a built-in function called

seq()that creates a list of numbers:seq(3)produces[1] 1, 2, 3,seq(2, 5)produces [1] 2, 3, 4, 5, andseq(2, 10, 3)produces[1] 2, 5, 8. Usingseq(), write a function that prints the n natural numbers:

r

print_numbers <- function(N) {

nseq <- seq(N)

for (i in seq_along(nseq)) {

print(nseq[i])

}

}

-

Exponentiation is built into R:

2^4. Write a function calledexpo()that uses a loop to calculate the same result. -

We can also apply some simple methods to R vectors. One of these is called

sort(). It works on numbers or letters:

r

sort(words)

## [1] "brown" "dog" "fox" "jumps" "lazy" "over" "quick" "the" "the"

r

sort(words, decreasing = TRUE)

## [1] "the" "the" "quick" "over" "lazy" "jumps" "fox" "dog" "brown"

Write a function called rsort() that does the same thing.

Ch-Ch-Ch-Changes

Data that can be changed is called mutable, while data that cannot be is called immutable. Like strings, numbers are immutable: there's no way to make the number 0 have the value 1 or vice versa (at least, not in R—there actually are languages that will let people do this, with predictably confusing results). Vectors, data frames, and matrices, on the other hand, are mutable: they can be modified after they have been created.

Programs that modify data in place can be harder to understand than ones that don't because readers may have to mentally sum up many lines of code in order to figure out what the value of something actually is. On the other hand, programs that modify data in place instead of creating copies that are almost identical to the original every time they want to make a small change are much more efficient. There are many ways to change the contents besides assigning to elements:

r

odds <- c(1, 3, 5, 7, 9)

odds <- append(odds, 13)

odds <- odds + 1

odds <- odds[-1]

odds <- sort(odds, decreasing = TRUE)

Challenges

- Write a function called total that calculates the sum of the values in a vector. (R has a built-in function called

sum()that does this for you. Please don't use it for this exercise.)

r

total <- function(vector) {

# calculates the sum of the values in a vector

sum <- 0

for (i in seq_along(vector)) {

sum <- sum + vector[i]

}

sum

}

Processing Multiple Files

We now have almost everything we need to process all our data files.

What we need is a function that finds files whose names match a pattern. We provide those patterns as strings: the character * matches zero or more characters, while ? matches any one character. We can use this to get the names of all the R files we have created so far:

r

list.files(pattern = "*.R")

## [1] "00-first-timers.Rmd" "01-starting-with-data.Rmd"

## [3] "02-func-R.md" "02-func-R.Rmd"

## [5] "03-loops-R.md" "03-loops-R.Rmd"

## [7] "04-cond-colors-R.md" "04-cond-colors-R.Rmd"

## [9] "05-testing-R.md" "05-testing-R.Rmd"

## [11] "06-best_practices-R.md" "06-best_practices-R.Rmd"

## [13] "07-knitr-R.md" "07-knitr-R.Rmd"

## [15] "guide.Rmd" "rblocks.R"

or to get the names of all our .csv data files:

r

list.files(path = "./data", pattern = "*.csv", recursive = TRUE)

## [1] "inflammation-01.csv" "inflammation-02.csv" "inflammation-03.csv"

## [4] "inflammation-04.csv" "inflammation-05.csv" "inflammation-06.csv"

## [7] "inflammation-07.csv" "inflammation-08.csv" "inflammation-09.csv"

## [10] "inflammation-10.csv" "inflammation-11.csv" "inflammation-12.csv"

As these examples show, list.files() result is a list of strings, which means we can loop over it to do something with each filename in turn. In our case, the something we want is our analyze() function. Let's test it by analyzing the first three files in the list:

```r filenames <- list.files(path = "./data", pattern = "*.csv", recursive = TRUE)[1:3]

for (f in seq_along(filenames)) { print(filenames[f]) analyze(file.path("data", filenames[f])) } ```

## [1] "inflammation-01.csv"

## [1] "inflammation-02.csv"

## [1] "inflammation-03.csv"

Sure enough, the maxima of these data sets show exactly the same ramp as the first, and their minima show the same staircase structure.

Challenges

- Write a function called

analyze_all()that takes a filename pattern as its sole argument and runs analyze for each file whose name matches the pattern.

To loop or not to loop…?

Intro sentence

#### Vectorized operations

A key difference between R and many other languages is a topic known as vectorization. When you wrote the total() function, we mentioned that R already has sum() to do this; sum() is much faster than the interpreted for() loop because sum() is coded in C to work with a vector of numbers. Many of R's functions work this way; the loop is hidden from you in C.

Learning to use vectorized operations is a key skill in R.

For example, to add pairs of numbers contained in two vectors

r

a <- 1:10

b <- 1:10

you could loop over the pairs adding each in turn, but that would be very inefficient in R

r

res <- numeric(length = length(a))

for (i in seq_along(a)) {

res[i] <- a[i] + b[i]

}

res

## [1] 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20

Instead, + is a vectorized function which can operate on entire vectors at once

r

res2 <- a + b

all.equal(res, res2)

## [1] TRUE

for() or apply()?

A for() loop is used to apply the same function calls to a collection of objects.

R has a family of function, the apply() family, which can be used in much the same way. You've already used one of the family, apply() in lesson 01 Starting with data.

The apply() family members include

apply()- apply over the margins of an array (e.g. the rows or columns of a matrix)lapply()- apply over an object and return listsapply()- apply over an object and return a simplified object (an array) if possiblevapply()- similar tosapply()but you specify the type of object returned by the iterations

Each of these has an argument FUN which takes a function to apply to each element of the object. Instead of looping over filenames and calling analyze(), as you did earlier, you could sapply() over filenames with FUN = analyze

r

sapply(filenames, FUN = analyze)

## Warning: cannot open file 'inflammation-01.csv': No such file or directory

## Error: cannot open the connection

Deciding whether to use for() or one of the apply() family is really personal preference. Using an apply() family function forces to you encapsulate your operations as a function rather than separate calls with for(). for() loops are often more natural in some circumstances; for several related operations, a for() loop will avoid you having to pass in a lot of extra arguments to your function.

Loops in R are slow

No, they are not! If you follow some golden rules.

- Don't use a loop when a vectorised alternative exists

- Don't grow objects (via

c(),cbind(), etc) during the loop - R has to create a new object and copy across the information just to add a new element or row/column - Allocate an object to hold the results and fill it in during the loop

As an example, we'll create a new version of analyze() that will return the minimum, maximum, and mean of the data from a file.

```r analyze2 <- function(filenames) { for (f in seq_along(filenames)) { fdata <- read.csv(file.path("data", filenames[f]), header = FALSE) res <- apply(fdata, 2, mean) if (f == 1) { out <- res } else { out <- cbind(out, res) } } out }

system.time(avg2 <- analyze2(filenames)) ```

## user system elapsed

## 0.009 0.000 0.009

Note how we add a new column to out at each iteration? This is a cardinal sin of writing a for() loop in R.

Instead, we can create an empty matrix with the right dimensions (rows/columns) to hold the results.

Then we loop over the files but this time we fill in the fth column of our results matrix out.

This time there is no copying/growing for R to deal with.

```r analyze3 <- function(filenames) { out <- matrix(ncol = length(filenames), nrow = 40) ## assuming 40 here from files for (f in seq_along(filenames)) { fdata <- read.csv(file.path("data", filenames[f]), header = FALSE) out[, f] <- apply(fdata, 2, mean) } out }

system.time(avg3 <- analyze3(filenames)) ```

## user system elapsed

## 0.009 0.000 0.009

In this simple example there is little difference in the compute time of analyze2() and analyze3(). This is because we are only iterating over 3 files and hence we only incur 3 copy/grow operations. If we were doing this over more files or the data objects we were growing were larger, the penalty for copying/growing would be much larger.

Note that apply() handles these memory allocation issues for you, but then you have to write the loop part as a function to pass to apply(). At its heart, apply() is just a for() loop with extra convenience.

Key Points

- Use

for (variable in collection)to process the elements of a collection one at a time. - The body of a for loop does not have to be indented, but should be for clarity.

- Use

length(thing)to determine the length of something that contains other values. c(value1, value2, value3) creates a vector- Vectors are indexed and sliced in the same way as strings and arrays.

- vectors are mutable (i.e., their values can be changed in place).

- Use

list.files(pattern)to create a list of files whose names match a pattern. - Use

*in a pattern to match zero or more characters.

Next Steps

We have now solved our original problem: we can analyze any number of data files with a single command. More importantly, we have met two of the most important ideas in programming:

- Use functions to make code easier to re-use and easier to understand.

- Use vectors and arrays to store related values, and loops to repeat operations on them.

We have one more big idea to introduce…